Joseph Albert Marcellus Blanchard

April 20, 2016

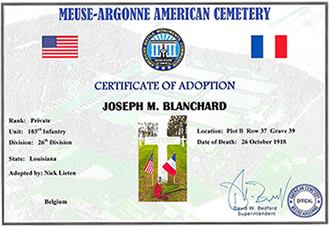

On 20 April 2016 I left a message on the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery Facebook page to ask if anyone needed a picture of a relative that is resting there in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France. A response came from Carolyn Ourso whose uncle has his final resting place on this cemetery. After exchanging pictures and details, I suggested to adopt the grave of her uncle Joseph and after meeting with the cemetery Superintendent I have officially adopted the grave of Joseph M. Blanchard.

|

Before the war

Joseph was born on the 11th of April in 1901 in New Orleans, Louisiana (USA), his parents where Joseph and Josephine. Sometime between his birth and 1910, the family moved from New Orleans to West Baton Rouge, probably in the town of Addis, Louisiana.

Louisiana, USA |

New Orleans |

Addis |

|

Joseph was nicknamed Buddy since his fathers name was Joseph too. His mothers name was Josephine.

He had six sisters, Amelia (1899), Pearl (1902, she was Earls twin sister but died shortly after birth), Ethel (1904), Juanita (1906), Norma (1907) and Claudia (1910) and three brothers, Earl (1902), Lawrence (1904, he died aged five) and John (1913).

In the army

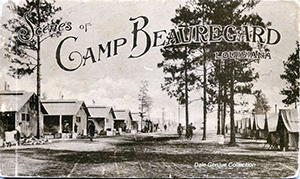

Camp BeauregardBuddy enlisted in Camp Beauregard, Louisiana on 27 September 1917

Camp Beauregard is a US Army installation located northeast of Pineville, Louisiana. It is operated by the Louisiana National Guard as one of their main training areas.

The camp was built in 1917, when the War Department authorized the building of more than thirty camps around the country to train troops for the First World War.

In 1919 the camp was abandoned and given to the state. In 1940 it was returned to the US government for use as a World War II training area. After the war it was returned to the state and used as a training area for two years before it was deactivated.

In 1973 it was reactivated and became one of the premier military training areas in Louisiana.

Buddy was in Company E, 1st Louisiana infantry, National Guard (later nationalized to Company E, 156th Infantry) from September 27, 1917 until May 18, 1918.

Camp Beauregard, Pineville, Louisiana |

Camp Beauregard, Pineville, Louisiana |

Camp Beauregard, Pineville, Louisiana |

|

June Automatic Replacement Draft

It is not very clear what the situation was between May 19 and July 5 of 1918. On the ship roster Buddy was listed as a member of the 156th Infantry, which made up part of the June Automatic Replacement Draft. So at one time, at least while on the ship, Buddy seemed to be a member of two organizations, but he gave his address as the June Automatic Replacement Draft so his membership in the 156th Infantry probably ended when he boarded the ship. It is hard to find out information about replacement drafts because in the early days when America entered the war, the had elaborate plans on keeping men together in groups when they were sent overseas and training them before sending them to the front lines.

156th Infantry |

Camp Merritt

Joseph probably arrived at Camp Merritt on June 3 or 4. Joseph describes his trip in a letter home in which you can hear the excitement of an 18 year old boy who has spent all of his life in the small town of Addis, Louisiana.

Camp Merritt was an embarkation camp near Hoboken, New Jersey. It was a camp where troops could assemble for ship transport to France. On average, the troops spent one day to two weeks at Camp Merritt before being sent to Hoboken to board ships for the European battlefields. In the course of war, more than 1 million US soldiers passed through Camp Merritt bound for Europe.

Camp Merritt, New Jersey |

Embarkation for Europe

On June 11, 1918, Buddy and the other soldiers embarked on the RMS Carmania in Hoboken, New Jersey. The ship sailed to Liverpool (Great Britain) on June 12 where it arrived on June 23, 1918. While on the Carmania, Buddy was still considered a member of the 156th Infantry. His rank was Private and he was a member of Company 11 Camp Beauregard June Automatic Replacement Draft Infantry.

RMS Carmania, a British ocean liner owned by The Cunard Liner |

As he landed in England, each soldier was given a letter signed by the King of England, which read:

"Soldiers of the United States, the people of the British Isles welcome you on your way to take stand beside the Armies of many nations now fighting in the Old World the great battle of human freedom. The Allies will gain new heart and spirit in your company. I wish that I could shake the hand of each one of you and bid you Godspeed on your mission. George, R I."

After their arrival in Liverpool, Buddy and the members of the Camp Beauregard June Automatic Replacement Draft went by train to Southampton. Along the way, hundreds of people may have lined the right of way as the train passed through many cities and towns. But the people lining the way were only women and children. No young men were seen, they had all gone to war.

The troops marched to an English rest camp on the edge of the city of Southampton where most remained two to five days. After this stay, the Americans crossed the English channel to France, most landing at Le Havre. This trip was usually at night because of the presence of enemy submarines and mines in the English Channel.

France

After an overnight stay at Le Havre, the soldiers traveled by train to a classification camp at Saint-Aignan. Here the newly-arrived soldiers were classified by divisions and furnished with full overseas equipment. After that, they waited until they were sent to their various companies.

Saint-Aignan was a replacement depot known to thousands of dough boys as "Saint Agony", it was a camp where much of the A.E.F. did extensive training.

Joseph was assigned to a training camp in or near the town of Contres. He was assigned to the 162nd Infantry, Company B. The 162nd Infantry was probably a training unit for new men just arriving in France. In this infantry unit, Joseph and his fellow soldiers were given their final training before going to the front to refill regiments that had losses.

Joseph and his fellow soldiers were billted in houses, barns or other buildings in the city. They trained for combat in the nearby countryside. They drilled everyday with Saturday and Sundays off. They got quite warm during the summer weather, especialy on days they were marching. One soldier wrote home that they experienced a lot of electrical storms during the month of July.

Contres is located in the south central part of France, about 120 miles from Paris. It's a small village in the department of Loir-et-Cher.

Contres, France |

162nd Infantry |

Pont Wilson

On the 14th of July, the national holiday of France, a new bridge, Pont Wilson, was inaugurated in the city of Lyon. The bridge was named after president Wilson of the USA. The 162nd Infantry was the only American division to represent the A.E.F. in Lyon along with troops from Italy, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Africa and Belgium.

The inauguration of Pont Wilson |

26th Division

Joseph trained with the 162nd Infantry from the time he arrived in Contres in July 1918 until August 27, 1918. Then he was assigned to the 103rd Infantry, Company M, of the 26th Division and was sent to the front lines.

103rd Infantry Regiment |

26th Division |

Officially this happened on the 28th August 1918, however a letter from him dated on August 17, 1918, gives his new address as the 103rd Infantry.

The 26th Division, or Yankee Division, was made up of soldiers from the New England States. The division suffered a loss of many of these original soldiers. Casualties were replaced by soldiers such as Joseph Blanchard. They came from other areas of the United States so it now was a division representative of many states and sections of the United States, not just the New England States.

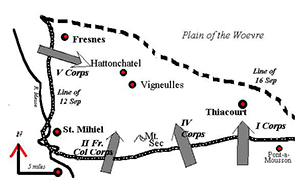

Saint-Mihiel Offensive

At the beginning of September, the 103rd Regiment broke camp and began the journey northward towards St.-Mihiel. They traveled a day and a night on the train. This was followed by a series of night marches. The regiment hiked three nights, camping wherever morning found them. They always camped in the woods to avoid being seen by the German aviators. The men then rested for four days and then continued the trip for three more days, arriving at a point near the lines.

On September 8, 1918 the 26th Division entered the front line as part of the 5th Army Corps. Company E of the 101st Engineers were assigned to the 103rd and 104th Infantry Regiments. In preparation for the upcoming attack, four working parties from Company E went out into No Man's Land from 9 PM until midnight. Their task was to cut paths through the wire or blow it up with torpedoes and to search for and to destroy German traps and mines.

On the 11th of September, prior to the attack that would begin the St.-Mihiel Offensive, orders for the 103rd Infantry Regiment were delivered late. As a result, much needed reconnaissance of the battlefield and liaison with adjoining units was delayed or hurried. Moreover, amunitions for the Stokes mortars did not arrive, and clips for the automatic rifles had to be carried in sand bags. The 103rd Machine Gun Battalion arrived late. Communication with the rear was poor, due to shortage of telephone wire.

The roads were very heavy due to an incessant rainfall of several days duration before September 11. All roads leading to the front were blocked for long distances by traffic, which was not regulated. And on the night of September 11, rain fell in torrents and the night was very dark.

St.-Mihiel Offensive, September 12, 1918 |

American soldiers moving to the frontline, September 12, 1918 |

On September 12, 1918, the 103rd Infantry Regiment went over the top. This drive lasted for two days. The infantry was eliminating whatever resistance they encountered. These units were ordered to advance abreast on the left of the division sector. The terrain was extremely difficult to pass over because it was pitted with old trenches and covered with tangled masses of old wire. The ground was very muddy.

The countryside was mostly wooded. The weather the first day was awful. It had rained the night before and continued all day long. The worst part was the hills. The men had to cross hills, up one steep bank and down the next. The barbed wire tore some of the men's leggings all to pieces. The men's clothes were not in good shape after the drive. The roads were poor and the advance so fast that the rolling kitchens didn't catch up with them that evening when they halted due to darkness.

The next day Joseph and the rest of the 103rd Infantry had to seize the towns of Saint-Maurice-sous-les-Côtes, Billy-sous-les-Côtes and Vieville-sous-les-Côtes, at the eastern base of the Heights of the Meuse. During the advance, the battalion took some fire from snipers and machune guns located in the Foret-de-la-Montagne. These were easily brushed aside or captured. Very few men were hit, and those who were were mostly not badly wounded.

Apparantly the enemy was in full retreat and the battalion marched in the direction of Saint-Maurice. The advance was somewhat slowed by the battalion from the 104th Infantry coming into the 103rd Infantry's sector and marching over the road leading to Saint-Maurice.

Around noon the leading elements of the 103rd Infantry reached the heights near Saint-Maurice and occupied the destroyed towns of Billy-sous-les-Côtes and Vieville-sous-les-Côtes which was done immediately. The 2nd Battalion occupied these two towns. The 1st and 3rd Battalion (Joseph was in the 3rd) were in the woods on the heights directly behind. The Germans retreated and attempted to leave little but scorched earth behind for the Allies.

The town of Billy-sous-les-Côtes was found in ruins, having been burned by the enemy. The town of Vieville-sous-les-Côtes was practically in the same condition.

Saint-Maurice |

Billy |

Vieville |

Nevertheless, great quantities of stores were found in Billy-sous-les-Côtes. Members of Company E of the 103rd Infantry searched the town and found plenty of things to eat; sausages, corned beef, crackers, beef, jam... They also found a large quantity of tobacco and hundreds of kegs of German beer. But they also found cannons and machine guns and a lot of ammunition.

On the 14th of September the offensive was finished. There were 483 dead or wounded soldiers in the Yankee Division of whom 109 were killed in action or died of their wounds. This was considered as a relatively small number. The 26th took about 2.400 prisoners and captured a huge quantity of ammunition and equipment.

Troyon sector

Joseph's unit was relieved by the French army on the 16th September. They were relocated to the Troyon sector. They were to stay there until October. The 103rd Infantry was subjected to very heavy shelling and gas in this area, depending on where they were located. On the plain, they were subject to gas, in the rear they were frequently shelled.

From the 19th September the 103rd held the front line in the Troyon sector for ten consecutive days. On the 24th five men were killed by shellfire in Combre-sous-les-Côtes and five men were seriously wounded.

On September 25, the 103rd Infantry, 26th Division was back in the thick of fighting and would remain there until Armistice Day. As a diversion of the Meuse-Argonne attack, the 26th Division was assigned to enemy towns of Marcheville and Riaville. These towns were to be assaulted on the morning of September 26 and held for 24 hours. During this raid, Joseph's battalion remained in its outpost position. An outpost position is a station established at a distance from the main body of an army to protect it from a surprise attack.

The next few days the men were gassed and shelled several times, several men got killed or seriously injured. Luckily Joseph wasn't among them. On the 30th of September Private Charles Miller was slightly gassed. He was sick and went to hospital but went back to confinement when he was better. He was the man that was with Joseph when he got killed about one month later.

Meuse-Argonne Offensive

From that day until October 4, the sector settled down a bit. A few men got sick from gas. On the 5th the Americans sent some mustard gas to the Germans and a day later they were relieved by the 79th Division and the French and Dismounted Cavalry Division. The regiment moved north of Verdun to take part in the last great battle of the war, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

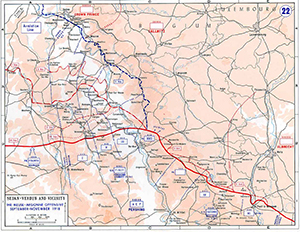

Meuse-Argonne Offensive, September 26 - November 11, 1918 |

American soldiers during the Argonne Offensive in October 1918 |

The troops marched by night. The movement was difficult due to bad conditions of the roads and the sheer number of troops begin concentrated in the area for the upcoming offensive. The 26th Division went into Army reserve near Verdun to rest and refit on October 7. They arrived in Sivry-sur-Meuse, 15 miles north of Verdun, on the 8th. Conditions were severe. Influenza was prevalent, the rain was almost continuous, shelter was insufficient.

The 26th Division was concentrated in and near Verdun and passed into army reserve. The 26th was a member of the 17th Corps. The 17th Corps as well as three French Divisions was charged with the duty of protecting of protecting the army's right flank and extending its success easterly and northeasterly by clearing the enemy from his very strongly held positions on the Cotes de Meuse above Verdun.

From September 17 until October 9 the 26th Division suffered 799 casualties. 139 dead and those who had died of their wounds. Nearly three fourths of them were in the 102nd and 103rd Infantry Regiments.

On October 10, 1918, the 26th Division took over the sector from the 18th French Division and a part of the American 29th Division. Fighting was serious and worse fighting was yet to come. Division headquarters was opened in the battered citadel in Verdun with the troops located in camps and billets to the south west.

Last letter home

Joseph regularly wrote some letters home. On October 12, 1918 he wrote the last known letter he wrote to his family:

"Dear Mother and Father

I am writing you a few lines to let you know I am well. I rec'd your letter of the 12th of September, the day we went over the top.

Sure was thankful for the money you sent but I don't need it, it looks like real good money.

You say Charles Hebert is in France. Well that's good. Hope they all get a chance at it. I imagine it would look funny if I was at home and I wouldn't have to register and Jessie and all those small fellows would have to. I am glad I came now.

I wrote you a letter when we were on the other front. I also rec'd a letter from Amelia (his oldest sister) not long ago. I don't write to anyone but you all because it's hard to write. We hardly stay over four days in one place and we don't know what a train looks like. So you can imagine how much a fellow carry in his pack. One blanket and a shelter half and if we didn't need them very bad we would ditch them.

So tell Amelia and those that I will write when I can and for her not to stop writing. Tell Earl to write sometime. I like to know what he is doing and what kind of time he had at grandpas. I know you all don't welcome a letter more than I do. I am sending you two German postcards I got out of a dugout when we went over the top. That about all the souvenirs I could send in a letter. Everything is looking fine and everybody is looking forward to going home soon.

Well I carried this paper in my jacket over a week and this was in the center of the others so it is the best I could get.

[Next sentence is illegible because of tear in paper. The paper Joseph used was Y.M.C.A. paper bearing this letterhead: "On active service with the American Expeditionary Forces."]

So I will close with love.

From your devoted son.

I am sending you a German shoulder strap I cut off a dead German's coat."

The 103rd Infantry moved to Coté de l'Oie on October 14 in preparation to take over a sub sector on the line. The weather was rainy and cold and muddy. The men had no protection against the weather. Some of the men were under shell and machine gun fire and gas.

During the night, the 26th Division completed relief of the French 18th Division in the Neptune Sector from Ormont on the left to Beaumont on the right. The 52nd Brigade (Joseph's Brigade) held the right side of the line in a tangle of trenches north and northeast of Cote de Poivre. The 101st Infantry was given the left end of the line, on the crest of a hill. Next to the right was the 102nd Infantry, with the 103rd Infantry on another hill and the 104th Infantry in reserve. This sector was under severe and constant shelling, which made it extremely difficult to get supplies and ammunition. Even the back areas were sprayed by shells each day. American guns replied to the German bombardment, the resultant din was terrific.

On October 16 the 26th Division came up to reserve positions near Samogneux and Haumont. Back of the regiments of the 26th was their own artillery, heavily reinforced with French units. The strong smell of mustard gas everywhere in the Ormont sector indicated repeated gassing. It was an unhealthy place to be. The whole of the sector was under an almost perpetual gas atmosphere, with the French retaliating in kind. Unlike some American divisions, the 26th Division was not reluctant to use gas, it got small supplies almost daily.

October 18, 1918: making the way to the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The roads were narrow, many shell pocked. The roads were littered with bones, boots, cartridges, belts, rifles, tin cans... The nights were very dark. The 26th Division entered the line in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive north of Verdun, relieving the French 18th Army Corps and the 2nd French Colonial Corps. Encountering stubborn resistance, the 26th Division advanced slowly northeast and then east.

Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the locations where Buddy probably has been |

The following days the 26th Division pushed in the Argonnes forest as part of the 5th Corps, which was part of the American First Army. They went in well under strength. They also had lack of both junior and senior officers.

They set out from Sivry on October 21, advancing southeast through hill and valley country, covered with what once had been forest but now was now reduced to a wilderness of scraggly chunks of trees which rose from a honeycomb of shell holes. A ghastly waste included the German point of departure for their drive against Verdun, in which they would sacrifice more than half a million men. Bois d'Haumont, Bois de Ville and Bois d'Ormont are names that will live forever in the battle records of the Yankee Division.

General Clarence Edwards

The next day the 26th Division received its greatest blow on this day, one from which it never fully recovered. While General Clarence R. Edwards, the division's commanding officer, was organizing an attack to start the next morning, he received orders relieving him from his command. The men of the division were stunned. General Edwards had just taken over a sector on the worst part of the whole line. For three days he had suffered the most intense grief over the death of his only daughter, Bessie, who fell victim to pneumonia while working in a cantonment hospital in the United States, and his personal aide, "Nat" Simpkins was also at death's door from the same disease.

The order relieving the General stated that he was to be detached from the division and the A.E.F. and return home to train a new division. The most intense gloom settled down over the division as soon as the news became generally known. General Edwards was the one who stimulated the troops with his own indomitable spirit and caused them to go forward when it seemed that human nature could do no more. It was he whose unflagging optimism and cheery words lifted them up. It was their General who watched over them, cared for them, and saw to it that their lives were not unneccessarily sacrificed.

General Clarence Ransom Edwards |

The General's last fight

On the night of October 22, Colonel H.I. Bearss of the 102nd Infantry sent out an order announcing the attack on the following morning would probably be the last fight the men would have an opportunity to make under their beloved commanding officer, General Edwards. Colonel Bearss urged every man who was to take part to make the engagement a fitting climax to the brilliant record of General Edwards.

During the night all battalions of the 103rd Infantry moved into the front lines, occupying old German positions which were in a bad state of repair. From the moment of its arrival on the line until the very end of hostilities, the 103rd Infantry was subjected to severe artillery fire. The weather was dismal with a continual rain and cold river mists saturating everything including clothing and blankets. Dugouts and trenches were flooded and knee-deep in mud, hillsides were mud piles torn by constant artillery and sniper fire, the roads were impassable, and toxic gas permeated everything.

Joseph's 3rd Battalion was to begin its movement when it saw a yellow rocket fired as a signal. Owing to the fierce German counter barrage, the observers did not see the signal. The ensuing delay was costly. Two officers of the 3rd Battalion were struck by shell fragments and one later died. Many of the battalion enlisted men who were awaiting orders were either killed or wounded by the German shelling and also tragically by some short friendly rounds.

The infantrymen in the 3rd Battalion lay in the open, anxiously awaiting orders to advance. The infantry was badly cut up. The division took part in local offensive operation - hard fighting. It took all objectives on time and 64 prisoners. About 300 were killed and wounded.

In spite of its losses, the 3rd Battalion finally went forward about noon and late in the day and finally reached the ridge but not before Sgt. Charles H. Alward, 101st Infantry Regiment, and several members of his platoon were killed by shell fire as he led them forward. With darkness coming on, the attacking force chose not to advance farther or to exploit the gains by continuing the attack into Bois de Bélieu. The men dug in for the night.

On this day General Edwards issued his goodbye order to his division. In it he thanked the men of the 26th Division for their loyalty to him and fo what the division had accomplished in the common cause. He noted that he left the division in full confidence that its same fine work would continue to the end.

The attack on Bois d'Haumont, Bois des Chenes, Bois d'Ormont, Bois de Bélieu and Hill 360

The 52nd Brigade where Joseph was in remained in place at Bois d'Haumont protecting the right flank. A conciderable advance was made. There were many changes in command in this period which affected the morale of the troops. The fighting continued for five days and nights, through underbrush and stumps that was old fighting ground. On every hand were skeletons of French and German dead, which had lain there unburied for several years. The artillery concentration was terrific and frequently caused the 26th Division to relinquish their gains, only to counter attack and retake them. The 101st Infantry fought back and forth across one strip of territory at least four times.

On October 23 the attack on Bois d'Haumont, Bois des Chenes and Bois d'Ormont, with Hill 360 at its eastern edge began. All the objectives were gained except Hill 360. At 7h00 in the morning of October 23, it was announced that the 26th Division had reached its normal and exploitation objectives. The Germans came back strongly at once. Under the pressure of a heavy counter attack, supported by intense artillery fire, the 101st Infantry Battalion, which had gone through Bois de Bélieu, was forced to relinquish its gain.

A day later the enemy was reinforced and partially relieved by fresh troops. The Americans started a new attack and once more a violent resistance was encountered. The enemy contested every inch of the American advance. By darkness, the Americans had penetrated Bois de Bélieu to a depth of 500 meters and further to the south advanced to the lower slopes of Hill 360.

Nights brought a new enemy reaction. Four furious counter attacks were directed in quick succession against the 101st Battalion. They were resisted succesfully, but the fourth attack pushed the Americans back again beyond the western edge of the Bois de Bélieu. The Americans reformed and returned to the attack at 2:30 am.

On October 25, following a violent interdiction and destructive fury by American artiller, the Americans took up their advance once more against Hill 360 and also moved again to penetrate and exploit the Bois de Bélieu. However, the enemy's resistance was not overcome. The 26th Division sustained a bombardment exceeding anything which they had ever undergone. High explosives and gas, mingled with machine-gun fire, created a hell in which they fought and struggled on for days.

October 26, 1918

This is the day Buddy was killed in action. The 26th Division held the front around Souilly along with 11 other divisions. The weather this day was cloudy. The visibility was poor to fair.

Death of Joseph Blanchard

Joseph's death was described by Private Charles Miller, a member of the 103rd Infantry who was with Joseph at the time:"I was in the dugout with him when a shell made a direct hit. He died shortly after he was hit. We were in support in Bois de Haumont on October 26, 1918.

Joseph was buried by the Chaplain in a cemetery near the town of Haumont, grave n° 35."

The Chaplain of the 103rd Infantry was Albert G. Butzer. He wrote Joseph's parents:

"I buried your son on the Verdun front. He was killed in action by a German shell while we were holding the front line in the region of Bois de Haumont and buried in a little American cemetery on the hillside near the town of Haumont in the Department of Meuse. The whole fight in that region will go into history as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive or popularly called the Second Battle of Verdun.

Your boy was buried with a military and Christian funeral service with the American flag spread over his body. The grave was well marked with a cross and metal name plate and the exact location sent to Graves Registration Service.

Permit me to extend to you again the sincere sympathy of the Battalion. God comfort you in your great sorrow and give you the hope of a reunion some day thru Christ who conquered death for all of us."

Chaplain Albert G. Butzer (courtesy of his grandson Albert G. Butzer III) |

In another correspondence to Joseph's family, Chaplain Butzer wrote:

"...Your son was killed outright and suffered no pain whatever. Death was instantaneous and I do not believe he ever realized that he was hit.

His personal belongs were sent by me to The Bureau of Effects, Gen. Hdq. and from there will be forwarded to you. It may take quite a while."

It's not sure if the family ever got Joseph's effects.

It's also not sure when the family was notified of Joseph's death. Usually the relatives receive a telegram when a serviceman is killed in the war. There's no known telegram in the family. It's possible it's somehow lost or thrown away. Joseph's sister Amelia wrote a letter to her parents on 'Thursday Noon' after being informed of Joseph's death by her husband Clarence.

This is the letter Amelia wrote to her parents:

"Dear mother and father

I was certainly shocked when Clarence came and told me about Buddy. I cannot make myself believe it, as I had never thought that he was killed. I had always so much hopes thinking he'd soon write, and come home again.

Mamma, it's certainly hard for us all to think how young he was , and such a fine looking boy to get killed but Bud certainly was brave and manly to go. And one thing, too, Bud was so willing; even on the last letter he wrote he wasn't sorry and discouraged, as he said he hoped every one could get a chance to go over.

He even said he was glad he went when he did.

Mamma, of course we find it so hard to think our Dear Loved One was killed, and so far away but Mamma we all know that he fought and gave his life for "Old Glory" and the Freedom of our Country.

Hoping to hear from you all soon. I must close as I can't write any more as Clarence Jr. is hungry.

I am Your Loving Daughter

Amelia

Love to all from all

Mamma, come when u can."

Joseph's death was reported in the Baton Rouge newspaper on a Wednesday or Thursday between October 26 and November 27, 1918.

Article where Joseph's death is mentioned, printed the day before Thanksgiving in 1918 |

Joseph now rests at the Meuse-Argonne American cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. His grave is located in plot B, row 37, grave 39. He rests among 14.246 other men who gave their life for our freedom. In this cemetery there are 268 Stars of David, 486 unknown graves and 9 recipients of the Medal of Honor. Among the 14.246 are also three children and several nurses.

Meuse-Argonne American cemetery, Romagne-sous-Montfaucon |

103rd Infantry Regiment, 26th Division

103rd Infantry Regiment |

26th Division |

Private |

The 26th Division was an infantry division of the United States Army. A major formation of the Massachusetts Army National Guard, it was based in Boston, Massachusetts for most of its history. Today, the division's heritage is carried on by the 26th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade.

The Division was formed on 18 July 1917 and activated on 22 August 1917 at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts. It consisted of units from the New England area (six states in the northeast of the USA: Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut).

The Division commanded two brigades comprising national guard units from the six states. The 51st Infantry Brigade contained the 101st and 102nd Infantry Regiments, while the 52nd Infantry Brigade contained the 103rd and 104th Infantry Regiments, together with supporting units. Shortly thereafter, the division commander, Major General C.R. Edwards called a press conference to determine a nickname for the newly formed division. Edwards decided to settle on the suggestion of "Yankee Division" since all the subordinate units of the division were from New England. The division approved a shoulder sleeve insignia with a "YD" monogram to reflect this.

The division was sent to Europe in World War I as part of the American Expeditionary Forces and saw extensive combat in France. They arrived on 21 September 1917 in Saint-Nazaire in France. It was the second division of the AEF to arrive on the Western Front at the time, and the first division wholly organized in the US, joining the 1st Division.

The division immediately moved to Neufchateau for training, as most of the division's soldiers were new recruits. The French forces helped with this training as they were more experienced.

The Division was present along the Chemin des Dames, Aisne-Marne Campaign, the Saint-Mihiel Offensive, and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

The Division spent 210 days in combat during World War I. They suffered 1.587 soldiers killed in action and 12.077 soldiers wounded in action. They returned to the United States and the division was demobilized on 3 May 1919 at Camp Devens, Massachusetts.

Contact

Finding contact with Joseph's relatives went very fluent. As a matter of fact, I had contact with his niece Carolyn before I had adopted his grave.In April 2016 I was about to visit the Meuse-Argonne American cemetery and posted a message on the Facebook page of the cemetery I asked if anyone requested a photo of a specific grave. Carolyn was one to answer my request. I was informed a while before about the possibility to adopt a grave at the Meuse-Argonne American cemetery so it came to mind to ask the Superintendent to adopt the grave of her uncle Joseph Blanchard, since she was so nice. But not before I asked her permission to do so, which she gave me.

So a few days later I went to the cemetery and talked to the Superintendent and we arranged that I could adopt the grave of Joseph Blanchard. I am very honored to have found Carolyn and to adopt the grave of one of many heroes of the First World War, buried in Roumagne-sous-Montfaucon.

She provided me with so much information and pictures about Buddy, which gave me the possibility to finalise this webpage about him. I wouldn't be able to share all this information without her assistance and permission. I cannot imagine the time she has spent researching the life of her uncle during the war, and the trip Joseph's mother made to visit his grave.

Thank you Carolyn and all the rest of your family I got to know by now. I will continue to commemorate Buddy and his comrades as long as I can.

Personal information

Private, U.S. ArmyArmy No 1.596.911

103rd Infantry Regiment, 26th Division

Entered service from National Guard Camp Beauregard, Louisiana on September 27, 1917

Born: April 11, 1901 in New Orleans, Louisiana

Hometown: New Orleans & Addis

Died: October 26, 1918 in Bois d'Haumont, Haumont-Près-Samogneaux (France)

Status: killed in action (KIA)

Buried in: Plot B, row 37, grave 39, Meuse-Argonne American cemetery, Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France

Awards: /

Family

Father: Joseph

Mother: Josephine

Brothers: Earl (1902), Lawrence (1904 - 1909), John (1913)

Sisters: Amelia (1899), Pearl (1902 - 1902), Ethel (1904), Juanita (1906), Norma (1907), Claudia (1910)

Josephine's journey

Joseph Blanchard was killed in action on October 26, 1918. According to the information the relatives have now, the news didn't get to the homefront until late November 1918. The U.S. Government issued daily reports of casualty lists – killed, wounded, missing, etc., which were published in local newspapers. Buddy’s name is listed on a late list of World War I Casualties of Americans Overseas Reported on November 27, 1918, so the family may not have heard about his October 26 death until late November, unless they received a telegram earlier than that. For me it's unimaginable how it feels to lose a child, so I can't write down how Josephs mother Josephine must have felt when she received the news. Joseph's mother was able to visit his grave in September 1930 when the US Government sponsored trips to mothers and widows with sons/husbands buried overseas. You can read all about Josephine's journey to France to visit her son's grave on this website, or on the lovely Facebook page created by Carolyn, just click on the picture of Josephine standing at her son's grave for the website version, or the close up photo of Josephine for the Facebook page, it's well worth the visit. Website version |

Facebook page 'Josephine's Journey' |

More pictures

Joseph Blanchard

Grave

Sources

Any information you can provide me about this soldier, can be mailed to me (nicklieten at hotmail.com). Thank you.