David Worth Loring

April 28, 2014

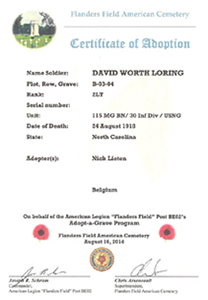

At the beginning of 2014 I contacted the responsibles of the Flanders Fields American Cemetery in Waregem to enquire about the possiblity to adopt a soldiers grave. They told me they were working on it and I immediately volunteered to adopt a grave. A few weeks ago I was able to officially request for a grave so I asked if it was possible to adopt the grave of David Worth Loring because I had stopped by his grave before. Today I finally received the confirmation of my adoption so I immediately started looking for more information about him. |

Before the war

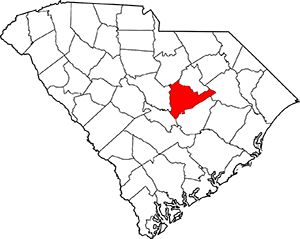

David Loring was born on March 20, 1887 in Sumter County, South Carolina in the United States. His parents were George W. Loring and Annie Nessfield Loring. George was born in Alabama, South Carolina, while Annie was born in North Carolina. South Carolina, USA |

Sumter County, South Carolina |

David went to Chauncy Hall school in Waltham, Massachusetts. He was a tremendous student and went to the University of South Carolina in 1905 and 1906. He found a job at the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and moved to Wilmington, North Carolina.

North Carolina, USA |

New Hanover County, North Carolina |

While working and living in Wilmington, New Hanover county, North Carolina, David met his future wife Viola who was 8 years younger than him. They got married in the house of Viola's uncle, Rev. W. M. Shaw in Wilmington on 26 April 1916. Together they had one son, but he was not viable and died a day after his birth, on 16 January 1917.

David W. Loring and his wife Viola (assumed), April 1918, Camp Sevier |

When David was killed, his father was the only one left. He died in 1920. David's wife remarried a man named Lars (or Thorbald) Peders. He was the captain of a steamer. They had one child together, Thomas.

At the cemetery in Sumter, a statue was erected to commemorate David. This was probably organized by his father, shortly after the war ended.

In the army

David first joined the 2nd Infantry Regiment of the South Carolina National Guard shortly after his mother died.When America went to war, he enlisted again in Wilmington, North Carolina. He was quickly promoted to 2nd Lieutenant but was later disapproved for medical reasons. David was determined to serve his country and decided to undergo surgery.

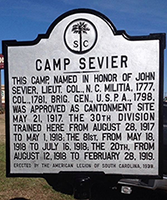

After surgery he re-enlisted on 23 October 1917 as a Private and was quickly promoted to 2nd Lieutenant again on 29 December 1917. After training in Camp Sevier, South Carolina, 2nd Lt Loring was sent to Europe in May 1918. He embarked in Hoboken on 11 May on the SS Haverford, an American transatlantic liner.

Camp Sevier, South Carolina |

SS Haverford |

Several of his letters he wrote home were kept. On 15 July 1918 he wrote a remarkable letter to his father. He admired the shooting and bombs that dropped on the battlefield. He literally wrote: "I believe this 'hunting' over here for big game is more fun than hunting deer in Santee Swam at home". He also wished for his relatives to be with him when they were putting a heavy barrage on the enemy, he wanted them to witness what he saw.

115th Machine Gun Battalion |

He also told his father about the presence of f'lying machines', being around as common as a Ford in the USA. David sometimes even saw fifteen at a time and spoke about one plane doing stunts above their camp.

In a letter dated 6 August 1918 David writes about him sleeping in a comfortable bed with sheets at the HQ, while on a billeting trip. how his commanding officer was buried in earth after an explosion threw sand all over his hideout. Luckily he was able to crawl back out unharmed.

He wrote about the ongoing artillery barrages around him. Each time he feared one of his men's position was hit, he went out to check if everyone was ok. One time he was out to check on his men, a shell fell right next to his hut. But it was this concern for his men that was fatal to him on 23 august 1918.

Two days before he was fatally wounded, he wrote to his aunt Anna that he was enjoying himself pretty well at the moment, and that the men fixed his dugout up with a cot, table, chair, Morris chair, lamp, vase full of fresh flowers, stove and hat rack. They found some Collards and cooked it for him and the boys, which they enjoyed well.

Death of David Loring

David died on August 24, 1918 in Kemmel, Belgium in an action that he got awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. From his citation:"The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Lieutenant (Infantry) David Worth Loring, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 115th Machine-Gun Battalion, 30th Division, A.E.F., near Ypres, Belgium, 23 August 1918. When his gun positions were rendered untenable by shell fire, and his men were ordered to seek shelter in dugouts, Lieutenant Loring left a place of safety for the purpose of seeing that all his men were under cover and was mortally wounded by a shell, dying on his way to the hospital."

David Loring was first buried at the Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery in Poperinge, before he was interred at the Flanders Field American cemetery in Waregem, Belgium.

Flanders Field American cemetery, Waregem, België |

115th Machine Gun Battalion, 30th Division

115th Machine Gun Battalion |

30th Division |

Second Lieutenant |

The 30th Division was called the Old Hickory Division. Within it were three infantry battalions, the 117th, 118th and 119th and three machine gun battalions, including David’s 115th.

The following summarizes the activities of the 30th Division during the war. It is borrowed from R. Jackson Marshall’s book, Memories of World War I: North Carolina Doughboys on the Western Front (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1998) and from Elmer A. Murphy & Roberts S. Thomas, The Thirtieth Division in the World War (Lepanto, AR: Old Hickory, 1936, 342 pp).

World War I lasted between 1914 and 1918. American working people had a tradition of detesting European wars. Some had migrated to the United States to escape conscription. Typically, Thomas Jefferson and Congress in the Trade Embargo Act of 1807 stopped American trade with Europe to prevent our being drawn into the Napoleonic Wars. It was only the mercantile interests that wanted intervention.

The 30th Division that David Loring would soon join had just returned from the U.S.-Mexican border when the division was called into federal service on 25 July 1917. It was ordered to Camp Sevier, near Greenville, South Carolina, to prepare for war. In October a contingent of draftees arrived to increase the division to full wartime strength of about 27.000 men.

In May 1918 the division traveled to New York and soon left for Europe. After a two-week voyage, the division landed in England, and then departed for France. The 30th Division was assigned to the American 2nd Corps, and attached to the British Army. In June 1918 the division underwent extensive combat training under British supervision, and exchanged American for British equipment and firearms.

On 2 July 1918, the 30th Division was sent to the British 2nd Army in Belgium. On 16 August, "Old Hickory" replaced British troops on the front in the trenches near Ypres. While there the division attacked and captured German positions with a loss of 37 dead and 128 wounded. Among those killed was David Loring. About a week after David died, the division on 3 September withdrew from the front and transferred to the British 4th Army. By 25 September, the 30th Division held its position opposite the German Hindenberg Line near Bellicourt, France. This was called the Cambrai-St. Quentin front. At 5h50 on 29 September the 119th and 120th infantry regiments, which were part of the 30th Division, went "over the top" supported by British tanks against the enemy lines.

Despite high casualties, the 30th Division broke through the Hindenburg Line. By that afternoon, Australian troops passed through the 30th Division and carried on the attack. The attack made by the 30th Division was a tremendous success. The division was credited as the first to break the Hindenburg Line. In addition to a large cache of enemy arms and equipment captured, about 47 German officers and 1.432 soldiers were taken prisoner. For these spoils and the 3.000-yard advance made against enemy lines, the division suffered about 3.000 casualties. This was the greatest loss for North Carolina-South Carolina since the Civil War.

The next day the division was pulled out of the battle, but "Old Hickory" returned to the front on 5 October. The 30th Division engaged in severe fighting off and on until 19 October, when it received orders to withdraw from combat for the last time. From July through October, the division suffered 1.641 killed, 6.774 wounded, 198 missing, and 27 taken prisoner, for a total of 8.415 losses.

For the remainder of October and until the cease-fire ended the fighting on 11 November 1918, the 30th Division was being reorganized. After the war it remained in France and was not part of the Army of Occupation. In April 1919 the 30th Division soldiers were sent home and discharged.

Contact

While researching the life of David W. Loring in April 2014, I found much information, with one source leading me to the e-mail address of Elizabeth G. I sent her an e-mail and was delighted to hear she was related to David W. Loring.David Loring was the fist cousin of Elizabeth's grandfather. Her father was born in 1908 and was a big admirer of David so we can imagine what a shock it must have been losing him in that horrible war.

Personal information

Second Lieutenant, U.S. ArmyService # ?

115th Machine Gun Battalion, 30th Division, C Company

Entered service from Wilmington, North Carolina

Born: March 20, 1887

Hometown: Sumter, Sumter County, South Carolina

Died: August 24, 1918 in Kemmel, Belgium

Status: died of wounds (DOW)

Buried: Plot B, row 3, grave 4, Flanders FIeld American Cemetery, Waregem, Belgium

Awards: Distinguished Service Cross

Distinguished Service Cross |

Family

Wife: Viola Fennell (Shaw) Loring (1893-1976)

Son: Unknown name (1917 - died one day after birth)

Father: George Washington Loring (1852-1920)

Mother: Annie Nessfield Green Loring (1858-1907)

Brother: /

Sister: Carrie C. Loring (1882-1890), Mary L. Loring (1885-1886), Dorothy N. Loring (1894-1894)

More pictures

David Loring

Grave

Flanders Field American Cemetery

Memorials

Sources

Any information you can provide me about this soldier, can be mailed to me (nicklieten at hotmail.com). Thank you!